It might be surprising to think about browsing for therapists and ordering up mental health care the way you can peruse a menu on Grubhub or summon a car on Lyft.

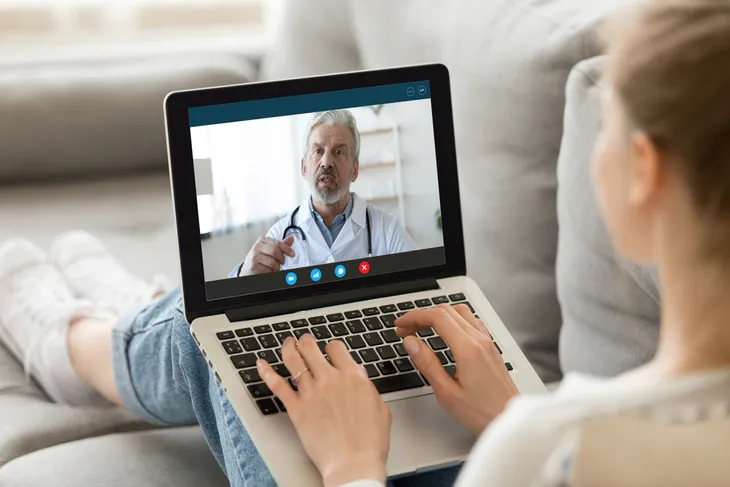

But over the last decade, digital access to therapy has become increasingly common, in some cases replacing the traditional model of in-person weekly sessions between a therapist and client.

Apps for mental health and wellness range from mood trackers, meditation tools and journals to therapy apps that match users to a licensed professional. My team’s research focuses on therapy apps that work by matching clients to a licensed professional.

As a social work researcher, I am interested in understanding how these apps affect clients and practitioners. My research team has studied the care that app users receive. We have talked to therapists who use apps to reach new clients. We’ve also analyzed app contracts that mental health professionals sign, as well as the agreements clients accept by using the apps.

Real questions persist about how apps are regulated, how to ensure user privacy and care quality and how remote therapy can be reimbursed by insurance. While those debates continue, people are regularly using apps to connect to therapists for help with emotional and mental struggles. And through these apps, therapists are interacting with people who may never have considered therapy before.

A ready-made market

In the first year of the pandemic, rates of depression and anxiety increased by 25% worldwide. In a June 2020 survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 40.9% of respondents reported at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition, compared to only 19% in 2018.

The old model of therapy, in which therapists and patients sat face to face, was already out of reach for many. In fact, mental health apps are a response to the demand from clients seeking more accessible therapy services.

The COVID-19 pandemic turbocharged both trends – the growing need for mental health care and using technology to access it. For existing mental health clients, stay-at-home orders closed clinics and therapists’ offices to in-person visits, resulting in an unprecedented shift to online access to therapy.

How matching apps work

Consumer mental health platforms like Better Help, Alma and TalkSpace match clients to licensed therapy providers. With advertising on television, across social media channels and on highway billboards, the apps promote flexibility, convenience and the potential to receive support with slogans like “You deserve to be happy” or “Feeling better starts with a single call.”

When app users enter a platform’s online space, its proprietary software offers a digital dashboard and communication tools. These platforms also promise instant access to a professional therapist, immediate responsiveness from them as well as anonymity.

App users choose a therapist by reviewing a list of providers accompanied by thumbnail photos, resume-like bios and consumer reviews. Users also choose how they’ll connect with therapists – phone or video calls, email, text or some combination. The apps also let clients change therapists at any time.

As the client and their chosen therapist connect and communicate, behind the scenes the app collects and maintains records, later calculating the chosen therapist’s payment and billing the app user.

Apps and their risks

Curiously, while mental health app platforms promote themselves as providers of mental health services, they actually don’t take responsibility for the counseling services they are providing. The apps consider therapists to be independent contractors, with the platform acting as a matching service. And the apps can help users find a more suitable fit if they request it.

But no law or precedent protects consumers or clarifies app users’ rights. This differs from face-to-face therapy, in which practitioners work under the oversight of state licensing boards and federal law. Some of the major therapy apps have been accused of mining client data and being at risk for data breaches.

Like other virtual spaces, online mental health service domains operate under ever-evolving and localized regulations.

Who benefits from these apps?

The social workers our team interviewed talked a lot about who can benefit from this kind of app-based therapy and – importantly – who can’t. For example, the platforms are not set up to treat people with serious mental illness or mental disorders that substantially interfere with a person’s life, activities and ability to function independently.

Similarly, app-based psychotherapy is not suitable for those having suicidal thoughts. The platforms screen users for risk of self-harm when they sign up. If a client ever poses harm to themselves or someone else, user anonymity on the apps makes it almost impossible for a therapist to send a crisis response team. App-based practitioners told our research team that they sometimes end up monitoring their clients for signs of crisis by contacting them through the app more frequently. It’s one reason app therapists, who also screen users, sometimes reject potential clients who may need a higher level of care.

For those without severe mental illness, app-based therapy may be helpful in matching clients with a professional familiar with a range of problems and stressors. This makes apps attractive to those with anxiety and mild to moderate depression. They also appeal to people who wouldn’t ordinarily seek out office-based therapy, but who want help with life issues such as marital problems and work-related stress.

The apps could also be practical and convenient for those who can’t or won’t get formal therapy, even remotely, from a mental health clinic or office. For instance, the anonymity of apps might appeal to people suffering from conditions like social anxiety or agoraphobia, or for those individuals who can’t or won’t appear on a video call.

Therapy apps have helped to normalize the idea that it’s OK to pursue mental health treatment through nontraditional routes. And with high-profile people such as Michael Phelps and Ariana Grande partnering with these apps, they might even be on their way to making mental health treatment cool.

Lauri Goldkind, Associate Professor of Social Work, Fordham University

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.