Low back pain (LBP) is the second most common complaint heard by primary care physicians in the US. Approximately 85-percent of the US population has experienced LBP at least once in their lifetime. Most episodes of LBP occur in the lumbar, or waist, region of the spine, which supports most of the weight of the upper body. It is composed of five vertebrae, or backbones (L1-L5). Symptoms requiring urgent evaluation of LBP include loss of bowel or bladder function, leg weakness, and fever. Fortunately, most cases of LBP, regardless of cause, resolve in two to four weeks. Twelve causes of LBP include…

1. Sprains and Strains

Sprains and strains account for the majority (70-percent) of acute LBP (lasting two to four weeks). A sprain represents a stretching or tearing of ligaments, while a strain represents a stretching or tearing of muscle or tendon. Both can occur as a result of improper lifting or simply lifting an object that is too heavy.

Treatment of sprains or strains is conservative (non-surgical) and may include over-the-counter (OTC) pain relievers (acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or naproxen), muscle relaxers, bed rest, and short-term use (less than two weeks) of narcotic pain relievers, or opioids. Bed rest is debatable, as studies have shown more than a day or two can actually make pain worse.

2. Degenerative Disc Disease

Degenerative disc disease (DDD) is a fairly common cause (10-percent) of acute LBP (lasting two to four weeks). It is usually a consequence of normal aging or less frequently trauma. In DDD, the normally pliable disc between vertebrae (backbones) loses its elasticity. The disc loses its ability to cushion forces on the spine causing individuals to experience stiffness and LBP. Individuals with DDD have periodic flare-ups of LBP that do not get worse over time.

Most cases of DDD are best treated with non-surgical methods. Pain may be addressed with OTC pain relievers (acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or naproxen), muscle relaxers, and a short-term prescription (less than two weeks) for narcotic drugs (opioids). Chiropractic manipulation, ultrasound, and massage have also been reported as helpful in the treatment of DDD. Lastly, epidural steroid injections (ESI) and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may be helpful for DDD-associated inflammation and pain.

3. Ruptured Disc

A ruptured, or herniated, disc is attributable to four percent of all causes of LBP. The flexible disc between the vertebrae, or backbones, becomes compressed and ruptures. As a result, increased pressure may be placed on the spinal nerves (lying behind the disc), which leads to LBP. Individuals may also experience lower extremity numbness and/or weakness.

Most cases of a ruptured disc respond well to conservative treatment with bed rest, OTC pain relievers (acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or naproxen), muscle relaxers, a short-term (less than two weeks) course of narcotic pain relievers (if needed), and physical therapy (PT). Epidural steroid injections may be helpful to control inflammation and ease pain in subacute (four to 12-weeks) to chronic (greater than 12-weeks) LBP. As a last resort, surgery may be needed to remove all or a portion of the diseased disc.

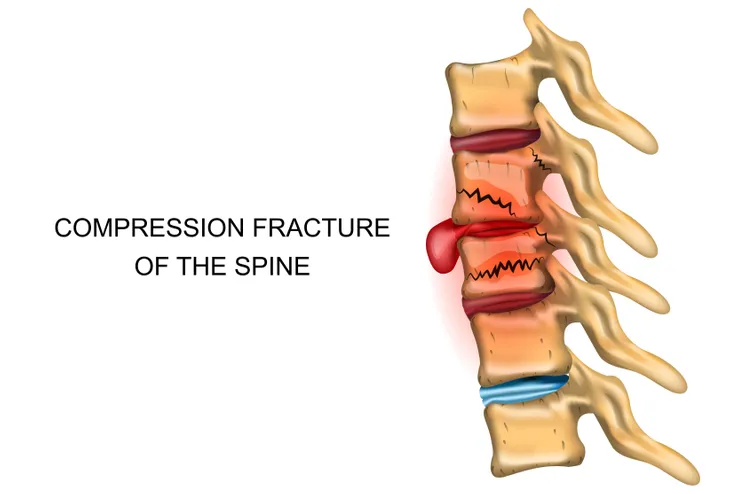

4. Spinal Compression Fractures

Spinal compression fractures contribute to four percent of all causes of LBP. Osteoporosis, which is thinning and weakening of bone, is the most common cause of this type of fracture. Healing of spinal compression fractures may lead to kyphosis, a hunch-like curvature of the spine, which is sometimes referred to as a “dowager’s hump.” Loss of height, sometimes six inches or more, is also a clinical clue to this diagnosis.

Most cases of LBP caused by spinal compression fractures respond well to conservative measures such as bed rest, OTC pain relievers, a short-term course of narcotic pain relievers (if needed), and PT. Surgery may be needed for extraordinary cases of LBP caused by spinal compression fractures. Surgical techniques include vertebroplasty (injection of cement into fractures), balloon kyphoplasty (injection of cement into fractures after height restored with balloon), and spinal fusion (permanently joining two or more backbones).

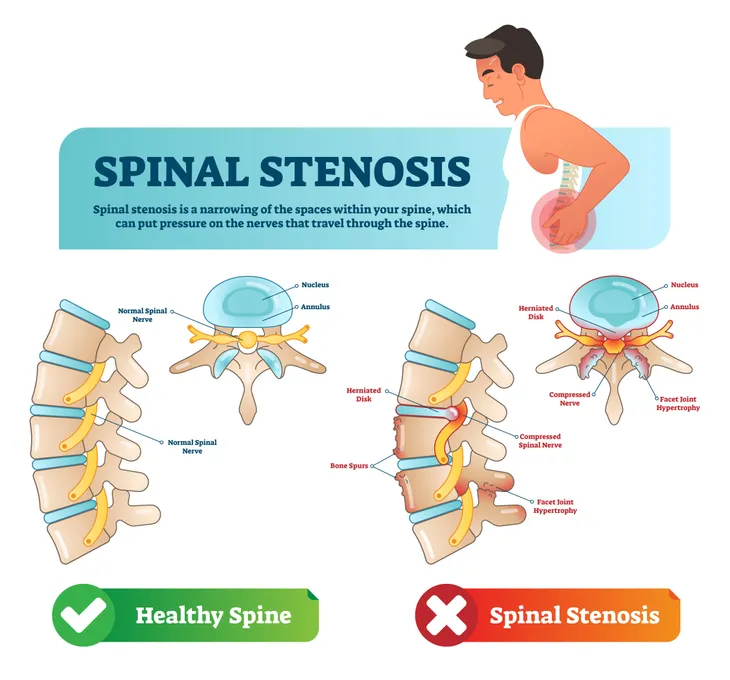

5. Spinal Stenosis

Spinal stenosis refers to narrowing of the bony spinal column leading to increased pressure on the spinal cord and nerves, which causes LBP. Associated symptoms may include leg weakness and loss of sensation. Spinal stenosis accounts for three percent of all causes of LBP. It is most commonly caused by arthritis of the spine, which leads to bony overgrowths called spurs. The growth of these spurs leads to narrowing of the spinal column.

Treatment of spinal stenosis is primarily conservative (non-surgical). The pain of spinal stenosis may be addressed with activity modification, OTC pain relievers, muscle relaxers, a short-term course of narcotic pain relievers (if needed), PT, gabapentin (an anti-seizure medication that desensitizes nerves), and antidepressant medications. In rare cases, surgical decompression of the spinal nerve may be needed to relieve pain.

6. Sciatica

Sciatica refers to compression of the sciatic nerve, the large nerve originating just below the buttocks and extending down the back of the legs. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the human body. Sciatica accounts for less than one percent of all causes of LBP. It causes LBP typically described as burning or shock-like, which may radiate down the back of the leg and into the foot. Associated symptoms may include numbness and weakness in the affected leg.

Treatment of sciatica is typically non-surgical. Individuals may respond to heat/ice, OTC pain relievers (acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or naproxen), muscle relaxers (if needed), and short-term use of narcotic pain relievers (if needed). In severe cases, epidural steroid injections may help by decreasing inflammation. Alternative treatment of sciatica may involve acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation, massage, and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). Most cases of sciatica resolve in six to 12-weeks. Recurrence may be decreased or prevented with PT and home exercises.

7. Spondylolithesis

Spondylolithesis accounts for less than one percent of all causes of LBP. It refers to a condition characterized by a vertebra, or backbone, slipping out of place and compressing spinal nerves in the region. Spondylolithesis is usually a consequence of normal aging and less commonly trauma. Compression of spinal nerves leads to LBP. Associated symptoms may include numbness or weakness in one or both legs.

Most episodes of LBP caused by sponylolithesis respond well to conservative treatment, which may include activity modification, OTC pain relievers (acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or naproxen), PT for core strengthening exercises, and weight loss. In rare cases, surgery may need to be performed to decompress the affected spinal nerve. Alternatively, surgery to fuse the affected vertebra to the vertebrae above and below may be performed.

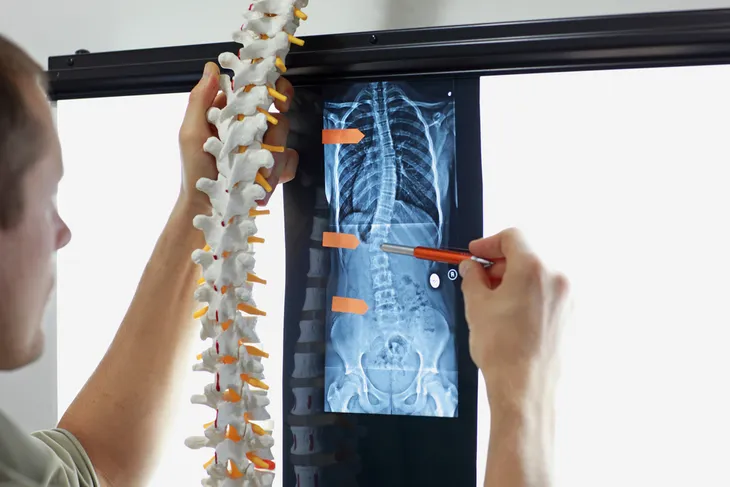

8. Scoliosis

Scoliosis accounts for less than one percent of all causes of LBP. It refers to a lateral (toward the side) curvature of the spine. Normally the spine is aligned in a straight vertical line. Idiopathic (no specific identifiable cause) is the most common type of scoliosis and most commonly affects adolescents ages 10 through 16. Overall, girls are more likely than boys to have the disease.

Treatment of scoliosis is usually dictated by the degree of spinal curvature. Bracing is the usual treatment for individuals with spinal curvature between 25 to 40 degrees. Bracing may halt the progression of spinal curvature seen. Surgery should be considered for individuals with spinal curvature greater than 40 degrees. Less than 0.1-percent of individuals with scoliosis have spinal curvature greater than 40 degrees. Spinal fusion (joining the vertebrae permanently) prevents worsening of spinal curvature and does not completely and perfectly straighten the spine.

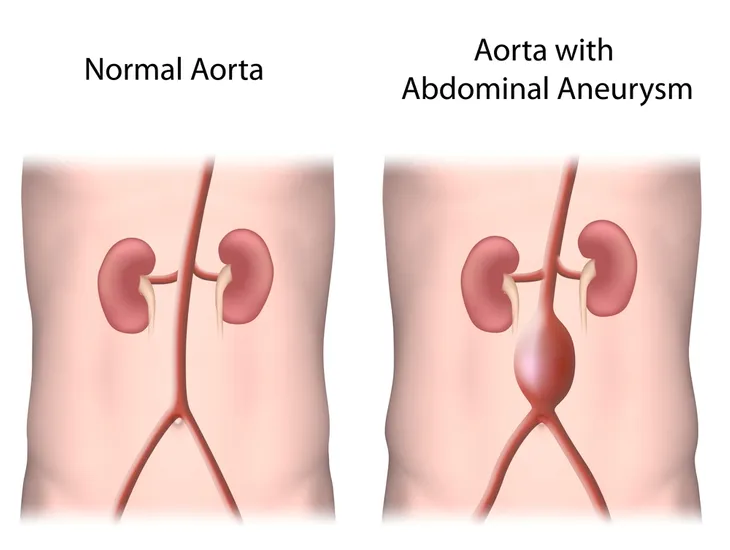

9. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Atherosclerosis (hardening of arteries with cholesterol-like plaque) can cause weakening of the wall of the aorta (largest artery in the body) leading to an abnormal bulge, or aneurysm. An aneurysm is most likely to occur in the abdominal portion of the aorta and is referred to as an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). The disorder is most often seen in males over the age of 60 with risk factors such as smoking and high blood pressure.

Most individuals with AAAs have no symptoms, but when the vessel leaks it can lead to LBP. Those individuals lucky enough to have their AAA discovered, before it ruptures, can be monitored. Surgical repair is typically recommended when the diameter of the aneurysm is greater than 5.5-cm. If needed, surgical repair is done with a graft of man-made material (often Gore-TexTM). A ruptured AAA has mortality, or death rate, approaching 80-percent. In other words, only 20-percent of individuals survive a ruptured AAA.

10. Kidney Stones

Kidney stones can be a cause of LBP. The pain is often described as sharp and one-sided (unilateral). Neprolithiasis is the medical term for kidney stones. Approximately one in every 20 people will develop kidney stones at some point in their lifetime. The LBP caused by kidney stones is usually accompanied by blood in the urine (hematuria). Dehydration is a major risk factor for the formation of kidney stones. The types of kidney stones are as follows: Calcium oxalate (80-percent), Calcium phosphate (5 to 10-percent), Uric acid (5 to 10-percent), Struvite (10 to 15-percent), and Cysteine (1 to 2-percent).

Most individuals with kidney stones are able to pass them through their urine, albeit painful. As a result, treatment of kidney stones is conservative and may include narcotics for pain relief and increased intake of fluids to facilitate passage of the stone. Kidney stones not able to pass through urine may need invasive procedures to aid in their passage. Lithotripsy utilizes sound waves to crush stones into very small pieces. Some stones have to be surgically removed, which is called a percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

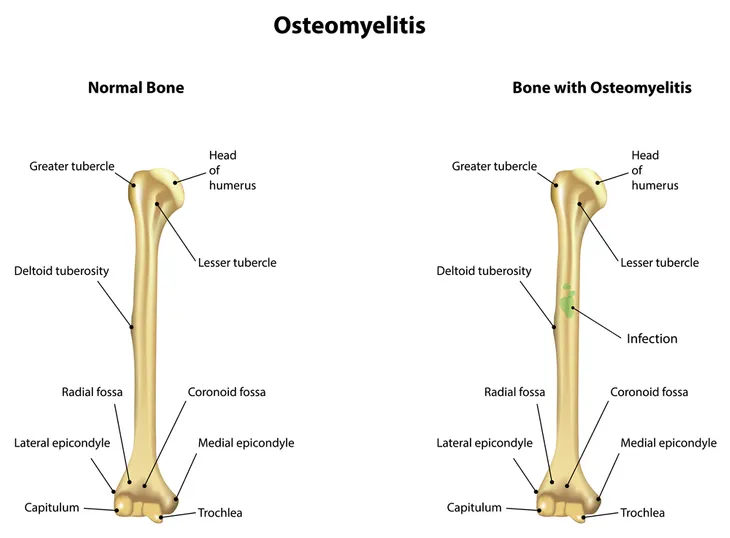

11. Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis refers to an infection of the vertebra, or backbone, and hence, can be a cause of LBP. Most cases of vertebral osteomyelitis involve the lumbar, or waist, region of the spine. The infection is usually transmitted via the blood and can be bacterial, viral, or fungal. The most common cause of vertebral osteomyelitis is the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus. Symptoms that may accompany LBP include fever, chills, swelling, weight loss, and nighttime pain worse than daytime pain.

Treatment of osteomyelitis is usually nonsurgical and involves a four to six week course of intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Bracing is another element of treatment for osteomyelitis. It provides spinal stability while the infection heals. Bracing may be continued for six to 12-weeks. Rarely, surgical decompression is needed for an abscess placing undue pressure on a spinal nerve. Fusion of the spine is usually performed simultaneously to stabilize the involved vertebra.

12. Shingles

Shingles, or herpes zoster, is an infrequent cause of LBP. Shingles is a viral infection that causes a painful rash. It can occur anywhere on the body, but most commonly appears as a singular stripe of blisters wrapping around either the left or right side of the torso without crossing the midline of the body. The same virus (varicella-zoster virus) responsible for causing chickenpox causes shingles. After an individual’s recovery from chickenpox, the virus lies dormant in nerve roots and is reactivated many years later causing shingles.

Anyone who has ever had chickenpox can develop shingles, which can be extremely painful. A vaccine is available to reduce the risk of shingles. The shingles vaccine (ZostavaxTM) is recommended by the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention for adults age 60 and older. Prompt treatment of shingles with antiviral drugs (acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir) can speed healing and reduce chances of complications such as postherpetic neuralgia, vision loss, facial paralysis, and skin infections.